Securing MCP Servers in Zero Trust Environments

MCP servers sit in the execution path between agents, tools, and data systems - this position makes them part of your control plane. If an attacker compromises an MCP server, they gain indirect control over tool execution, data access, and system behavior. Security design must treat MCP servers with the same rigor used for database engines, API gateways, and identity providers.

Most MCP security failures do not come from protocol weaknesses. They come from overly broad permissions, weak identity enforcement, missing runtime isolation, and poor audit visibility. Strong MCP security adheres to traditional distributed-system security principles.

Enforce identity first. Exercise least privilege access. Isolate execution. Log everything.

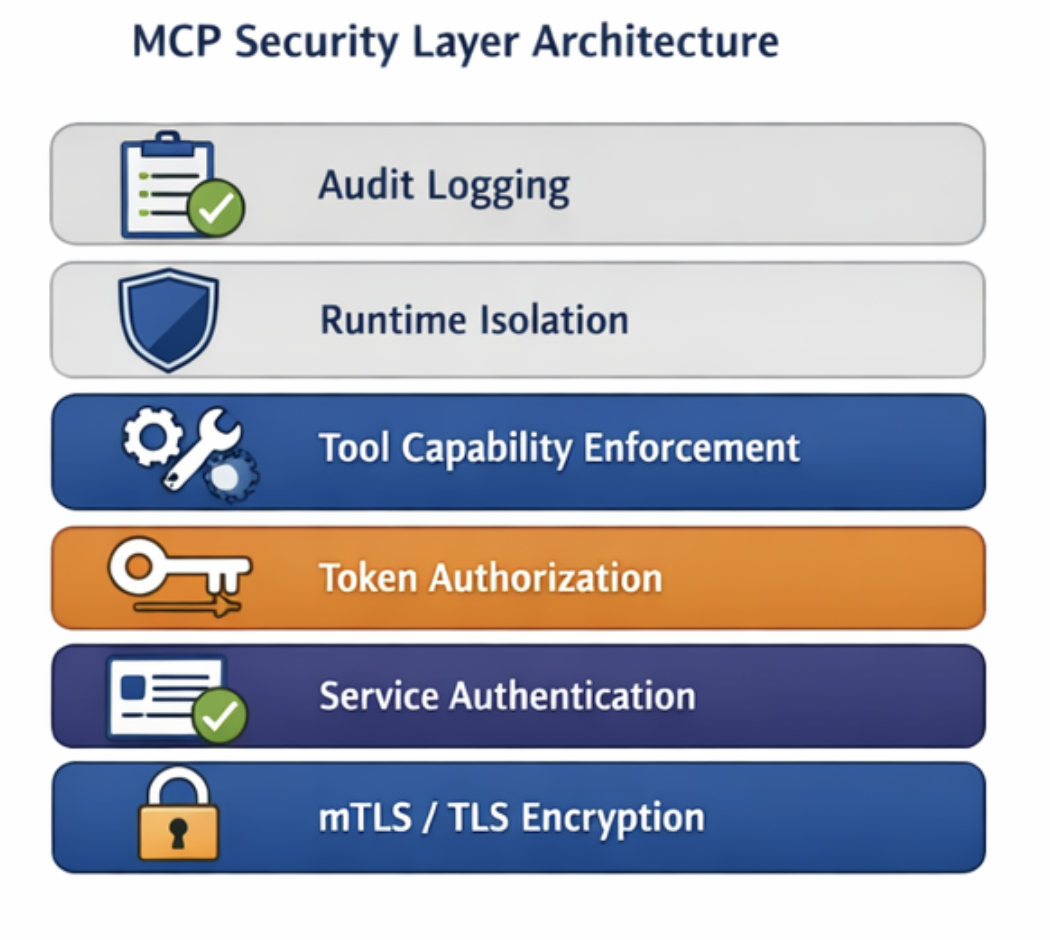

Mature systems design MCP security across five layers:

Tool capability modeling.

Token to tool authorization mapping.

Runtime sandbox isolation.

Tool supply chain validation.

Transport identity enforcement using TLS, mTLS, or tokens.

Tool Capability Model

Tool Capability Model

Every MCP tool exposes a narrow and explicit capability surface. Tools must never behave as generic execution endpoints because broad execution surfaces increase attack impact. Each tool must declare operation type, data scope, resource limits, and external side effects before registration. This model follows the long-established operating-system syscall design, where each operation runs within strict, predictable boundaries. Strong capability modeling ensures that compromise of a single tool or token does not expose the entire platform or data plane.

Capability definitions must be enforced at the MCP server boundary, not inside tool code. The MCP server must validate capability constraints before execution begins. Tools must assume that permission checks have already occurred and must not make trust decisions independently.

You should enforce:

Strict separation between read tools and write tools to prevent accidental data modification.

Clear separation between runtime tools and administrative tools to reduce privilege escalation risk.

Data scope restrictions at the tenant, schema, or dataset level to prevent cross-boundary data access.

Per tool CPU, memory, and execution time limits to prevent resource exhaustion or denial of service.

Explicit declaration of external side effects such as network calls or external system writes.

Token to Tool Permission Mapping

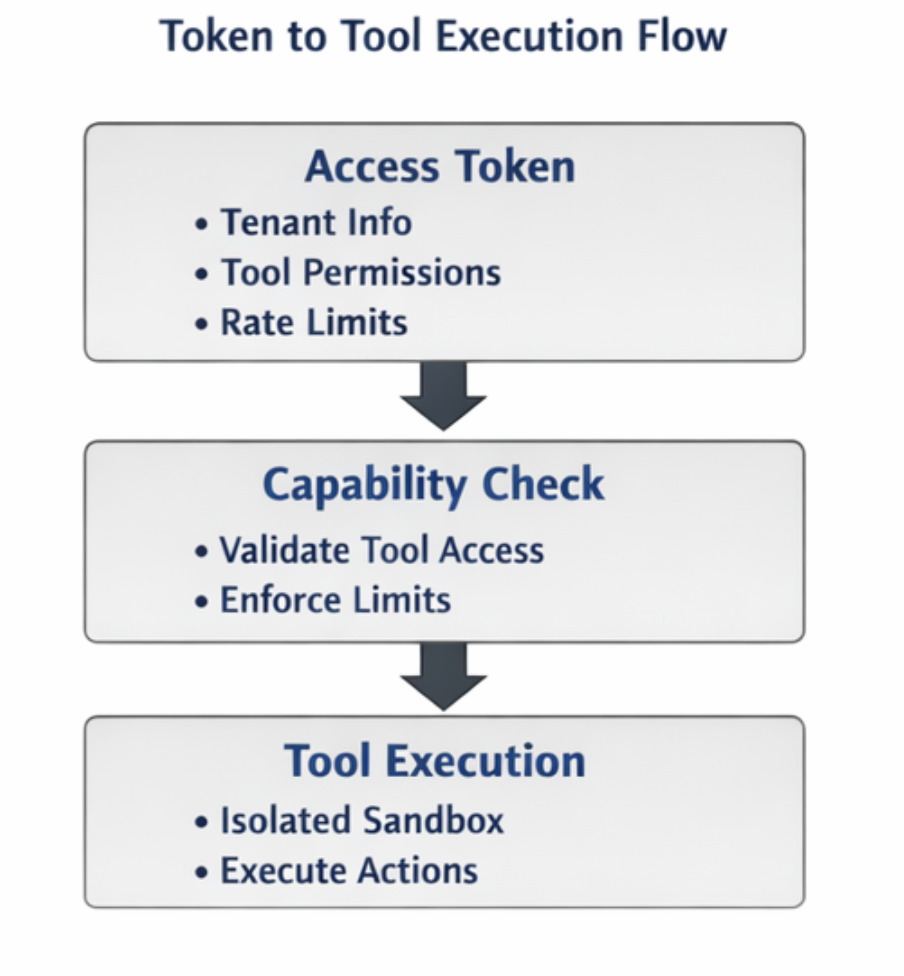

Identity determines who is making a request. Capability mapping determines what actions the request is allowed to perform. MCP security must bind tokens directly to tool permissions, not only to user or service identity. Authorization must be completed on the MCP server before tool execution begins. Tools must never perform their own authorization decisions because this creates inconsistent enforcement and increases the risk of privilege bypass. Strong systems treat tokens as permission containers, not only identity markers.

Each token must define a precise permission scope aligned with least-privilege principles. Tokens should never grant broad system access. Instead, they should restrict execution to specific tools, operations, and resource limits.

Each token should define the:

Tenant boundary to prevent cross-tenant data access.

Allowed tool list to restrict which tools the caller can execute.

Operation class (such as read, write, or administrative actions).

Request rate limits and concurrency limits (to prevent abuse or resource exhaustion).

Expiration and rotation policy (to limit long-term credential exposure).

Runtime Sandboxing and Isolation

Runtime Sandboxing and Isolation

Tools must never execute inside the MCP server process memory. Every tool invocation must run inside an isolated runtime boundary so a compromised tool cannot inspect MCP memory, inject code into the control plane, or extract sensitive data from neighboring executions. Isolation must assume tool code contains bugs or hidden malicious behavior and must prevent lateral movement across system components. Mature MCP environments treat tool execution the same way operating systems treat untrusted processes, with strict boundaries and enforced resource controls.

Common isolation models include container-based isolation, micro virtual machine isolation, and restricted-language runtime sandboxes with system-call filtering. The isolation layer must enforce strict runtime controls before tool execution begins and must not rely on tool code to enforce its own limits.

Isolation must be enforced:

• Filesystem access is blocked by default, with read-only access granted only when required.

• Outbound network access must be blocked unless explicitly whitelisted per tool and per endpoint.

• Disable shared memory access to prevent cross-process data leakage.

• CPU and memory quotas enforced per execution limits to prevent resource starvation.

• Enforce hard execution timeouts to terminate stuck or malicious tool processes.

Network access poses the greatest risk of data exfiltration. Any tool with unrestricted outbound network access creates a direct path for sensitive data to leave the environment. Production MCP deployments must treat network permissions as high-risk privileges and grant them only when strictly required.

Tool Supply Chain Security

Tools are executable code and must follow the same security discipline used for production application releases. Supply chain attacks target dependency managers, build pipelines, and artifact registries because they provide indirect access into production environments. MCP servers load and execute tool code, so any compromise in the tool build or distribution process becomes a direct execution risk. Strong MCP environments verify tool integrity before loading, during deployment, and again at runtime to ensure no tampering occurred between stages.

Secure tool lifecycle includes:

Signed tool artifacts during build to guarantee origin authenticity.

Signature verification during deployment to confirm the trusted publisher and integrity.

Hash verification before runtime execution to detect tampering or corruption.

Dependency vulnerability scanning to detect known security flaws in libraries.

Version pinning and provenance tracking to ensure deterministic builds and traceable history.

Tools must never download dependencies, plugins, or updates dynamically at runtime, as this bypasses security verification pipelines and introduces untrusted code into production execution paths.

Transport Identity and Authorization Layers

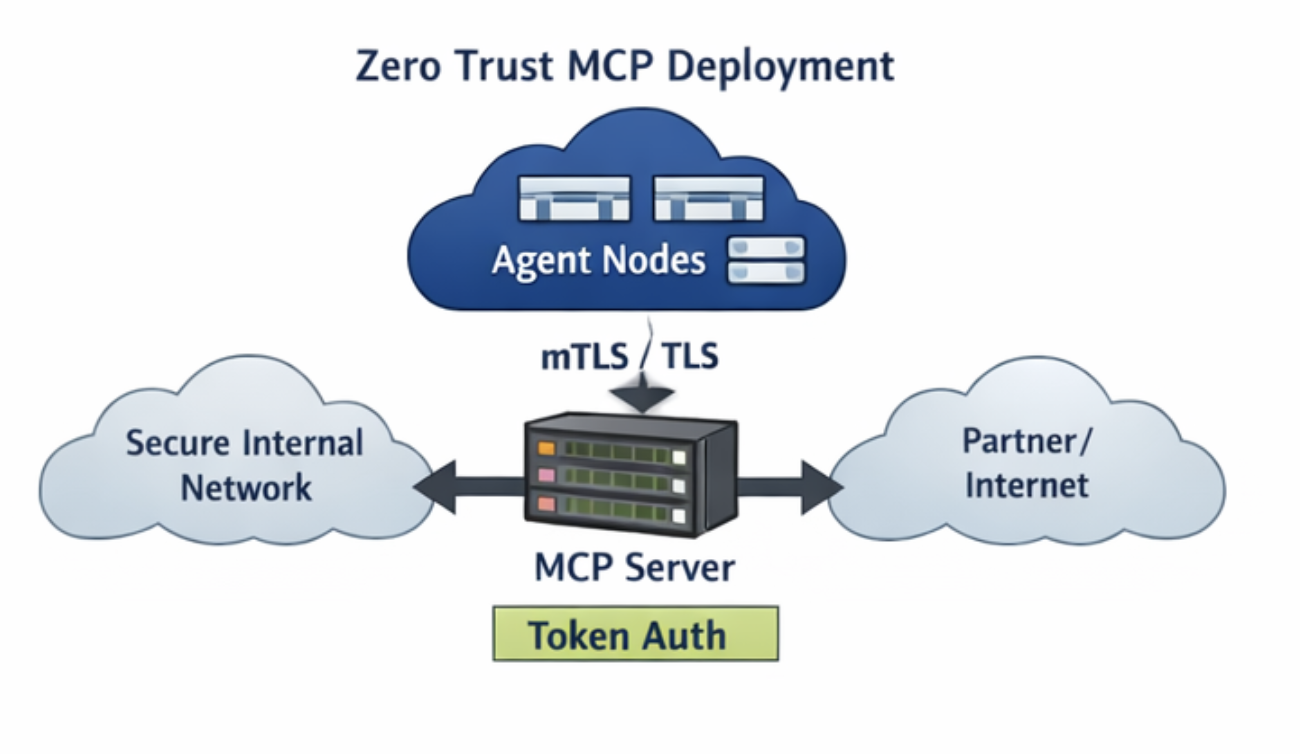

Transport identity and request authorization define two distinct trust boundaries within MCP systems. Transport identity confirms which service or workload establishes the connection. Request authorization confirms whether the caller has permission to perform a specific action. Secure MCP deployments combine both because connection trust alone does not guarantee permission safety, and request tokens alone do not prevent service impersonation inside internal networks. Mature systems treat transport identity as the outer security gate and token-based authorization as the inner permission-enforcement layer.

Transport identity relies on TLS or mTLS to verify the identity of the service connecting to the MCP server. Token authorization verifies tenant, user, or workload permissions at the individual request level. Together, they prevent both unauthorized service access and privilege misuse inside valid sessions.

Secure layered pattern:

mTLS verifies the calling service identity and prevents internal service impersonation.

The token verifies tenant, user, or workload authorization at request execution time.

Capability enforcement verifies tool-level permissions before execution begins.

Large-scale production deployments typically enforce mTLS for internal service-to-service communication while using token-based identity for external clients, partner integrations, and user-scoped workloads.

Audit Logging and Security Observability

Security without audit visibility fails during incidents. Every invocation of an MCP tool must generate a structured audit record.

Audit logs must include the following information:

Audit logs must include the following information:

Agent identity

Token identity

Tool name

Capability invoked

Execution duration

Resource usage

Execution result

Security teams rely on these logs for incident reconstruction, compliance validation, and anomaly detection.

Common MCP Security Failures in Production

Most MCP security incidents do not originate from protocol flaws or cryptographic failures. They originate from operational shortcuts taken during development, testing, or rapid scaling phases. Teams often relax security controls to speed up delivery, then forget to restore them before production exposure. Over time, these shortcuts accumulate into systemic risk. When attackers probe MCP environments, they typically exploit permission misconfigurations, weak isolation, or excessive trust between services rather than breaking encryption or the transport layer. These failure patterns repeat across industries because operational pressure consistently pushes teams toward convenience over enforced security boundaries.

Common failures include:

• Tools exposed without capability enforcement

• Admin tools accessible using runtime tokens

• Reused tokens across multiple tenants

• Long-lived tokens without rotation or expiration enforcement

• Sandbox isolation disabled during performance testing and never restored

• Tools have allowed unrestricted outbound network access, enabling data exfiltration

These patterns appear across organizations regardless of programming language, cloud provider, or infrastructure model because the root cause is process discipline, not technology choice.

Operational Security Discipline

Strong MCP security depends on continuous operational enforcement, not one time configuration. Security controls must remain active throughout the system lifecycle, including development, staging, and production environments. Over time, environments drift, teams change, and new tools get added. Without automated enforcement, even well-designed security architectures degrade into weak configurations. Mature MCP deployments treat security controls as part of daily operations, similar to monitoring, backup verification, and incident response readiness.

Production MCP deployments must include:

• Automatic token rotation to limit your exposure window if credentials leak.

Strict rejection of expired or revoked tokens at the MCP boundary.

Real-time alerts when new tools are registered or existing tools change capability scope.

Detection alerts for abnormal tool usage patterns, such as sudden traffic spikes or unusual access timing.

Global rate limiting per tool to prevent abuse, resource exhaustion, or automated attack patterns.

Strict separation between administrative MCP endpoints and runtime agent MCP endpoints to prevent privilege escalation paths.

Separation of control and data planes remains critical.

Secure MCP Layered Defense Model

Mature MCP deployments rely on layered defense because no single control remains perfect under real-world attack conditions. Each security layer assumes another layer might fail and provides containment if a compromise occurs. This approach follows long-standing enterprise security design used in database systems, financial transaction platforms, and network control planes. Layered defense ensures that a transport security failure does not automatically grant tool-execution rights, and that a token leak does not automatically expose full-system capabilities. The goal is to achieve a controlled blast radius and rapid detection.

Security layers include:

Transport identity verification using TLS or mTLS to confirm connection-level trust.

Service identity validation to confirm which workload or service is making requests.

Token-based authorization to enforce tenant, user, and workload permissions per request.

Tool capability enforcement to restrict which operations each request can execute.

Runtime isolation sandboxing to prevent tool escape, memory inspection, and data exfiltration.

Audit logging and monitoring to provide traceability, anomaly detection, and incident reconstruction capability.

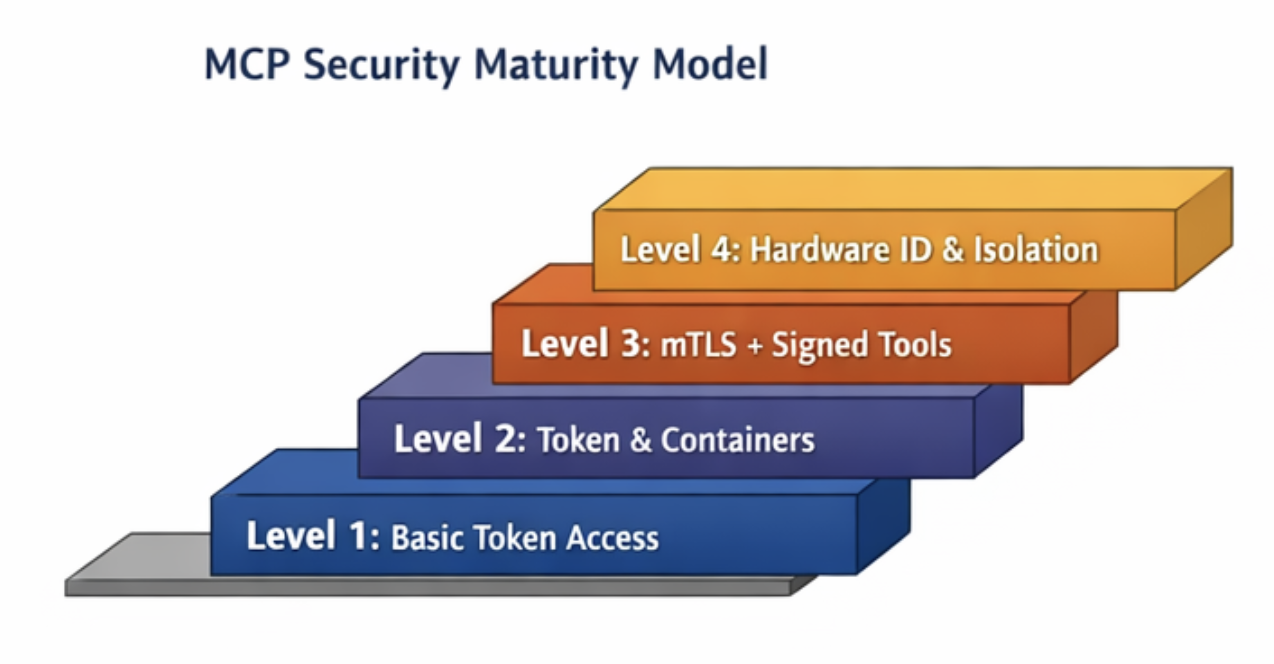

MCP Security Maturity Model

Level 1

Level 1

Level 1 represents early-stage MCP deployments in which security focuses solely on identity verification via tokens. Systems at this stage trust tools too broadly and assume internal services behave correctly. There is little separation between tool types, and runtime execution often happens inside shared processes. These environments rely heavily on perimeter security and developer discipline rather than on enforced technical controls. This level works for prototypes and early internal deployments but creates high risk once systems face real traffic, external integrations, or multi-tenant workloads.

Level 1 features:

Token-based authentication only

Broad tool permissions across the system

No runtime isolation or sandboxing

Limited or no audit visibility

High blast radius if the token is compromised

Level 2

Level 2 introduces structured authorization and basic execution isolation. Systems begin enforcing capability boundaries between tools and restrict access based on token permissions. Tool execution transitions to container-level isolation to reduce the risk of memory or file system escapes. Basic audit logging begins to track tool execution events. This level represents the minimum acceptable security posture for production systems handling internal enterprise workloads.

Level 2 features:

Token plus capability enforcement

Container-level runtime isolation

Basic audit logging for tool execution

Reduced blast radius through scoped permissions

Still vulnerable to supply chain and identity spoofing risks

Level 3

Level 3 represents mature enterprise MCP security. Systems combine transport-level identity via mTLS with token-based authorization at the user and tenant scopes. Tool artifacts become signed and verified before deployment and execution. A centralized capability registry controls tool exposure and permissions. Audit logging becomes comprehensive, supporting incident reconstruction and compliance reporting. This level supports regulated environments and large-scale multi-tenant deployments.

Level 3 features:

mTLS plus token-based authorization

Signed and verified tool artifacts

Centralized capability registry

Full audit visibility across the tool lifecycle

Strong protection against lateral movement inside networks

Level 4

Level 4 represents advanced zero-trust MCP environments. Identity expands beyond tokens and certificates into hardware-backed identity and workload attestation. Each tool runs in an isolated runtime environment, often using micro virtual machines or hardware isolation. Security systems analyze tool behavior patterns and detect anomalies in real time. Supply chain verification covers full dependency trees and build pipelines. This level appears in high-security industries, defense systems, and highly regulated financial environments.

Level 4 features:

Hardware-backed identity and workload attestation

Per tool runtime isolation environments

Real-time behavior anomaly detection

Full supply chain verification across dependencies and builds

Near-zero trust enforcement across the execution stack

Most production organizations operate between Level 2 and Level 3. They enforce capability controls and runtime isolation while continuing to evolve toward full supply-chain verification and hardware-backed identity. Mature security programs move gradually because Level 4 requires strong operational discipline, infrastructure investment, and security automation maturity.

pgEdge MCP Server for PostgreSQL

The pgEdge MCP server for PostgreSQL (available on GitHub) treats MCP as part of the database control boundary rather than a side helper. The server exposes SQL query execution, schema visibility, and database telemetry through MCP tools, so security starts with database credentials and then adds token or user authentication at the MCP entry layer.

The default behavior runs queries within read-only transactions, and project guidance warns against exposing them publicly because tool access provides broad schema and data visibility. TLS protects transport sessions, token auth restricts request-level access, and optional write modes require explicit enablement in newer builds.

In zero-trust environments, this design aligns with traditional database security principles: narrow tool surfaces, least-privilege tokens, strong audit logging, and strict network segmentation around the MCP service. Attackers love shortcuts more than developers, so treating MCP like core database infrastructure saves future pain.

Conclusion

MCP servers are becoming the core execution infrastructure for agent-driven systems, so their security posture directly determines system reliability, data protection, and operational trust. Secure deployments treat MCP servers as control-plane components and enforce layered defense through strong service identity, strict token-scoped authorization, narrow tool-capability boundaries, isolated runtime execution, verified tool supply chains, and complete audit visibility.

Systems built with these controls limit blast radius during failures, support forensic investigation, and maintain predictable behavior under real production pressure. Systems built without them eventually experience permission abuse, data exposure, or cross-tenant access during scale or attack events. Long-term stability comes from disciplined identity enforcement, least-privilege design, and continuous operational security enforcement across the entire MCP execution path.

If you want to get started with an MCP server for Postgres, check out pgedge-postgres-mcp on GitHub. Star the repository while you’re there to keep tabs on upcoming releases and new features